The Wild Backstory Behind the Noguchi Table

Plus, an ocean view case-study home for sale and 10 other fresh listings

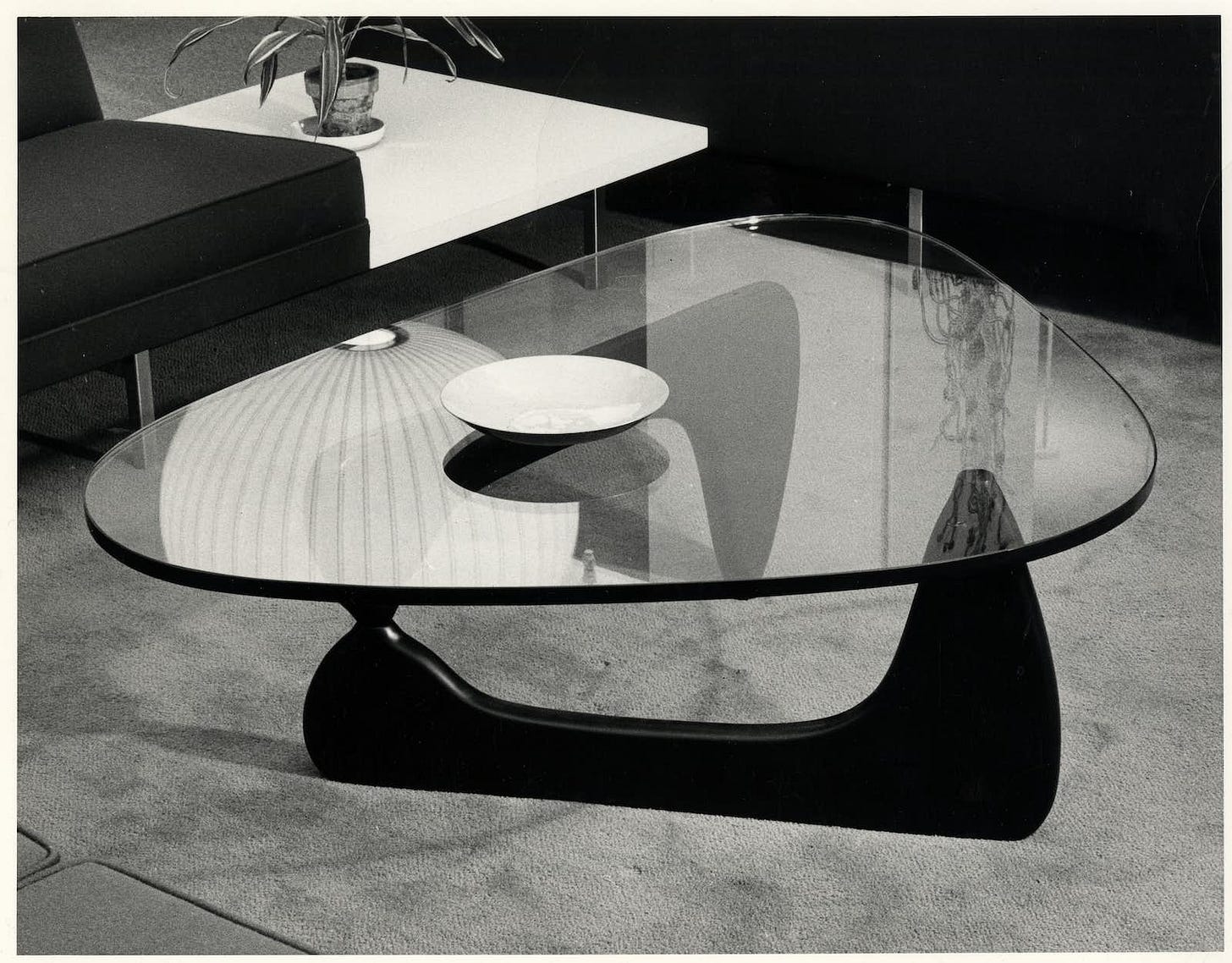

The Noguchi Table, first released by Herman Miller in 1948, is almost as recognizable as it is unique. Sometimes called the bi-morphic table, the design is a simple one, made from just three pieces: a free-form plate-glass top with flat polished edges, and a self-stabilizing tripod made of two interlocking curved legs of solid walnut. The table, an indisputable icon, almost didn’t happen though.

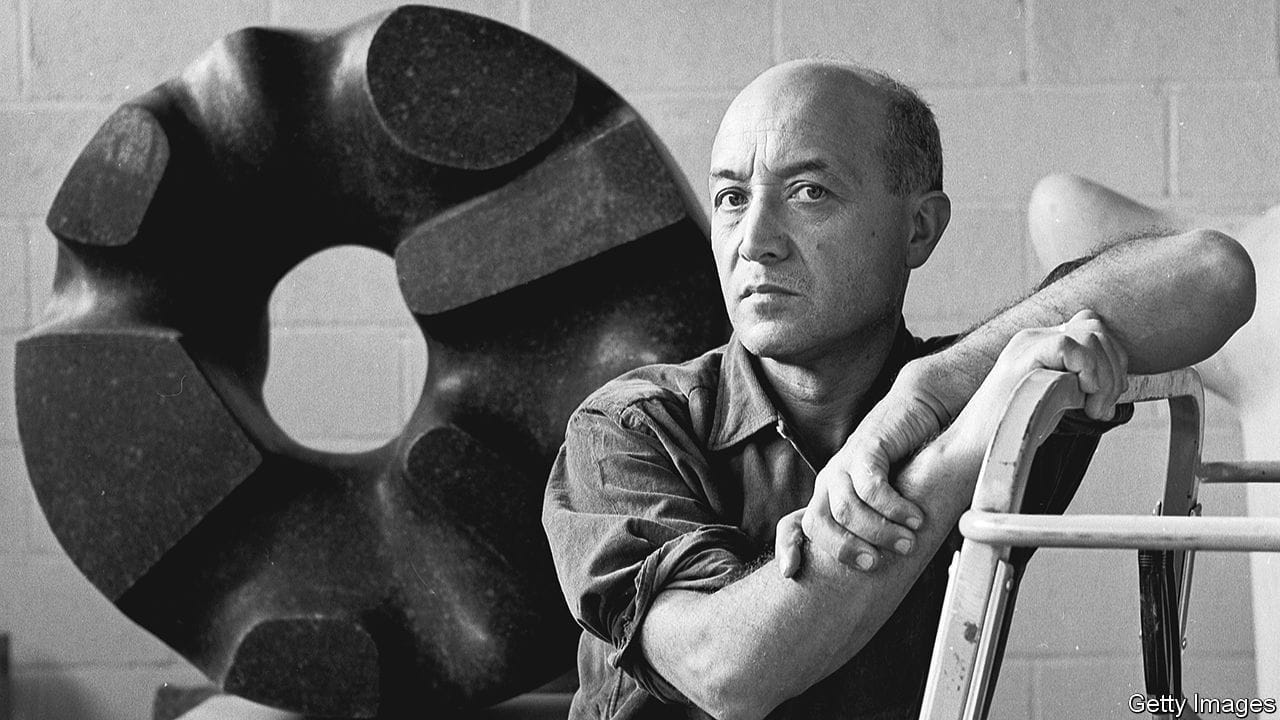

The son of a Japanese poet and an American writer, Isamu Noguchi was born in Los Angeles in 1904. Two years later, he moved to Japan with his mother before returning to the U.S. in his teenage years. After abandoning a pre-med program at Columbia University, Noguchi would go on to take sculpture classes on New York’s Lower East Side. The next decade included a Guggenheim Fellowship and extensive travel across Asia, Latin America, and Europe. Still far from commercial success, Noguchi survived on portrait sculpture and design commissions.

The story of that iconic table starts in 1939, when Noguchi designed a custom rosewood and glass table for A. Conger Goodyear, the President of the Museum of Modern Art. He submitted a similar version of that design in response to a request from British furniture designer T.H. Robsjohn-Gibbings, but never received a reply.

Everything changed however, when, in 1941, Pearl Harbor was attacked. The subsequent backlash and unjust internment of Japanese Americans affected Noguchi deeply and thrust him into the role of political activist. In 1942, he voluntarily left New York City to join his fellow Japanese Americans, intering himself at the Colorado River Relocation Center (Poston) internment camp. The artist hoped to teach arts and crafts classes to help improve conditions at the camp. His art supplies never arrived, and his design suggestions were ignored. While browsing a magazine, Noguchi discovered an ad for a table similar to his design, mass-produced by none other than Robsjohn-Gibbings, without credit or compensation.

Irritated by the theft of his design, Noguchi took action. Receiving a short-term furlough from the camp, he headed straight back to New York. Perhaps more motivated than ever before, he perfected his table design and teamed up with Herman Miller for production in 1947. The “Noguchi” table proved to be a massive success, outshining the copy-cat design of Robsjohn-Gibbings. Noguchi named the table after himself, of course, eliminating the possibility of anyone forgetting who had designed it.

Throughout a lifetime of creativity, Isamu Noguchi designed gardens and plazas, murals and fountains, furniture and paper lamps, and stage sets. When reflecting on his career, he noted that of all the designs he created, the table that bears his name represented his greatest success. To learn more, you can visit the Isamu Noguchi Foundation Garden and Museum in Long Island, New York.

“Everything is sculpture. Any material, any idea without hindrance born into space, I consider sculpture.”

Gems for Sale This Week

199 Chautauqua Blvd, Pacific Palisades, CA 90272 (Case Study House #18)

1210 Journeys End Dr, La Canada Flintridge, CA 91011

1437 Hillside Dr, Glendale, CA 91208

327 Manford Way, Pasadena, CA 91105

939 NE 114th Ave, Portland, OR 97220

1352 S Edison Way, Denver, CO 80222

2720 N Chelton Rd, Colorado Springs, CO 80909

14495 Foothill Road, Golden, CO 80401

1204 21st St NE, Austin, MN 55912

44 Cherokee Hls, Tuscaloosa, AL 35404

What a beautiful table